As discussed in the previous post, Greek and Roman religious

belief was that the dead inhabited an underground kingdom, overseen by various

chthonic deities such as Hades, Persephone and Charon. Unlike the

Judaeo-Christian tradition of a subterranean Hell dedicated to the punishment

of sinners (aka the burny fires, as my Presbyterian mum pleonastically called

it), the classical Underworld was the final destination of us all, good and

bad, just and unjust.

Punishment was certainly available for those who merited it,

however; and it was meted out in the place called Tartarus. According to

Hesiod’s Theogony (8th or 7th Century BCE), Tartarus

(originally created by the gods as a prison for the troublesome Titans) is situated

as far beneath us as we are beneath heaven:

τόσσον

ἔνερθ᾽

ὑπὸ

γῆς,

ὅσον

οὐρανός

ἐστ᾽

ἀπὸ

γαίης:

τόσσον γάρ τ᾽ ἀπὸ γῆς ἐς Τάρταρον ἠερόεντα.

ἐννέα γὰρ νύκτας τε καὶ ἤματα χάλκεος ἄκμων

οὐρανόθεν κατιὼν δεκάτῃ κ᾽ ἐς γαῖαν ἵκοιτο:

ἐννέα δ᾽ αὖ νύκτας τε καὶ ἤματα χάλκεος ἄκμων

ἐκ γαίης κατιὼν δεκάτῃ κ᾽ ἐς Τάρταρον ἵκοι.

τόσσον γάρ τ᾽ ἀπὸ γῆς ἐς Τάρταρον ἠερόεντα.

ἐννέα γὰρ νύκτας τε καὶ ἤματα χάλκεος ἄκμων

οὐρανόθεν κατιὼν δεκάτῃ κ᾽ ἐς γαῖαν ἵκοιτο:

ἐννέα δ᾽ αὖ νύκτας τε καὶ ἤματα χάλκεος ἄκμων

ἐκ γαίης κατιὼν δεκάτῃ κ᾽ ἐς Τάρταρον ἵκοι.

Hesiod, Theogony

721-725

…as far beneath the

earth as heaven is above earth; for so far is it from earth to Tartarus. For a bronze

anvil falling down from heaven nine nights and days would reach the earth upon

the tenth: and again, a bronze anvil falling from earth nine nights and days

would reach Tartarus upon the tenth.

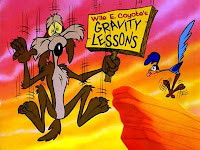

Incidentally, the Greek here for anvil (akmōn) has

the same root as the word acme (meaning summit or peak); a linguistic link serendipitously developed by

Chuck Jones some two-and-a-half millennia after Hesiod.

John Milton was probably alluding to Hesiod’s cosmology when,

in Paradise Lost, the Archangel Raphael tells of the rebel angels falling “nine

days” from Heaven into Hell. Milton presumably imagined that a rebel angel would

fall twice as fast as a bronze anvil: obviously he was unaware of Galileo’s then

recent proposal that bodies falling in a vacuum will fall with uniform acceleration.

Angel or anvil, nine days is an awful long time to be

falling. Obviously it is a poetic trope, an expression of the metaphysical distance

between the living and the dead, or the blessed and the damned. But to our

post-Galilean and post-Newtonian (and post-Jonesian) world, it seems

ridiculously exaggerated, not to say impossible. As a matter of interest, I

tried to work out roughly how far away Hesiod’s Heaven and Hell might actually

be if they were to be considered in terms of physical, rather than mythological

cosmology: unfortunately, my brain very soon began to overheat, what with having

to take into account the gravitational constant and all, so I gave up and am

going to rely on this guy’s calculation of 65,800 kilometers.

In order to then get to Tartarus, the anvil must presumably

fall through a hole in the Earth (diameter 12,742 km) and drop out the other

side. Assuming it landed with a splash at the entrance to the River Acheron, in

present–day Epirus, it would have popped out of the South Pacific antipode like

a Trident missile and end up in Tartarus after travelling a further 53,058 km

through space. Coincidentally (?), this is about the distance from Earth that a

putative space elevator would have to extend in order for an object attached to

it to achieve escape velocity.

To confuse matters even further, Virgil (never one to allow

Roman Epic to be outbid by the Greeks) claims that Tartarus is double this distance:

...tum Tartarus ipse

bis patet in praeceps tantum tenditque sub umbras

quantus ad aetherium caeli suspectus Olympum.

Aeneid VI 577-579

...Tartarus itself stretches down into darkness, twice the flying distance from heavenly Olympus.

...tum Tartarus ipse

bis patet in praeceps tantum tenditque sub umbras

quantus ad aetherium caeli suspectus Olympum.

Aeneid VI 577-579

...Tartarus itself stretches down into darkness, twice the flying distance from heavenly Olympus.

Milton’s Tartarus is even trickier to locate. A curious blogger came to the conclusion that an angel falling for nine days to Earth

would have to begin the drop somewhere on the far side of the Moon. Milton also

tells us that Hell is:

…As far removed from

God and light of Heaven

As from the centre thrice to th' utmost pole.

As from the centre thrice to th' utmost pole.

At first glance this would seem to suggest that the distance

from Heaven to Hell is three times the radius of the Earth, or 19,113 km. This would

imply that a rebel angel falls at 88.4 kph, which is coincidentally (?) just on

the legal side of the average speed limit on the real road to Hell*. So not

really very rebellious after all. Such calculations assume that Hell, as in the

classical tradition, is somewhere under the Earth’s crust. But in Paradise

Lost, the banishment of the rebel angels to Hell precedes the creation of

Earth: their “dungeon horrible” therefore cannot be terrestrial and

subterranean. Nevertheless, Milton’s pole and centre probably refer to the

distance from the Earth’s pole to the centre of Heaven.

|

| Blake: Casting the Rebel Angels into Hell |

So Milton follows, and trumps, the classical writers: in a

sort of poetic grade inflation, Hesiod locates Tartarus the same distance as

Heaven is to Earth; Virgil goes with twice that distance; and Milton three

times as far.

Our classical tourists in the Underworld, Odysseus and

Aeneas, have slightly different takes on the geography of the home of the damned.

In the Odyssey, Tartarus seems to be open-plan in the style of Camp X-Ray:

from his rocky viewpoint, Odysseus can observe the torment of various hubristic

ne’er-do-wells:

·

Tityos the giant (condemned to Tartarus for the attempted

rape of Apollo’s mother): he is stretched out on the ground and his liver is

eternally pecked by a pair of vultures.

·

Tantalus (food issues: he killed and cooked his own

son, then tried to serve Junior to the gods at a banquet): he is eternally

thirsty and hungry; he stands in a stream beneath a fruit tree, but is

prevented from consuming either.

·

Sisyphus (generally taking the piss out of the

gods, but in particular chaining up Death with the consequence that nobody

could die): sentenced to endlessly roll a stone up a hill, only to see it roll

back down again from the top.

|

| Sisyphus, Ixion and Tantalus |

The Aeneid, as always, has to be a bit more ornate: Tartarus

has triple walls, a massive iron tower and a gate made of toughened steel. Aeneas

can hear the howls of anguish and the crack of the lash, but is not permitted

to enter to see for himself. Luckily, his companion, The Sibyl, has previously had

a guided tour and fills our hero in on the various villains within. It is of

course a longer list than Homer managed, and includes in addition to the usual

suspects the hubristic ingrate Ixion.

Ixion, king of the Lapiths in Thessaly, was a thoroughly bad

lot. According to Pindar (Pythian Odes 2) and other sources, he was the first human

to kill his own relative (having murdered his father-in-law in a dispute about

money). He was shunned by all mankind for this crime, but Zeus took pity on him

and brought him home to Olympus. Ixion repaid the Zeus’ uncharacteristic good

deed by trying to seduce his wife, Hera. When the god found out about this, he decided

to deceive the deceiver by making a 3D model of Hera from a passing cloud: Ixion

promptly did the deed with this blow-up doll named Nephele, then boasted of his supposed success with

the goddess.

In punishment for this egregious breach of houseguest etiquette,

Ixion was bound to an eternally-revolving wheel of fire and dumped in Tartarus.

In an odd postscript, the nebulous sex-toy gave birth to the race of the

centaurs, half human and half horse.

|

| Rubens: Ixion and Nephele |

In the Aeneid, the Sibyl’s description of Ixion’s punishment

is a bit puzzling: she describes Ixion seated nervously beneath a tottering

rock; there is a banquet spread before him, but he is unable to reach it

because of a menacing Fury. This is the punishment associated with Tantalus:

almost all other sources (including Virgil himself in the Georgics IV 484) have

Ixion on a wheel. One commentator has explained the discrepancy away by

suggesting that the Sibyl is giving an impressionistic description of the

scene, “a confused sense of

terrors inextricably blended,” but this seems a bit like special pleading. Perhaps

even Virgil, like Homer, nods occasionally.

More about the ungrateful Ixion in the next post.

* Correction: the E6 now bypasses Hell and goes straight to

Trondheim airport.